Over the past few months, STH has been grappling with growth as well as refreshing our infrastructure at a number of facilities. As a lot of folks know, I will run things in production after we review them and well before many other enterprises do. Still, I have noticed that while we have adopted Arm in some areas (some AI servers and DPUs, namely), for our main compute and storage, we have not. As a summer piece, I wanted to give some insight as to why, since I think it highlights a bigger challenge of adopting Arm in the enterprise data center.

For this, we also have a video:

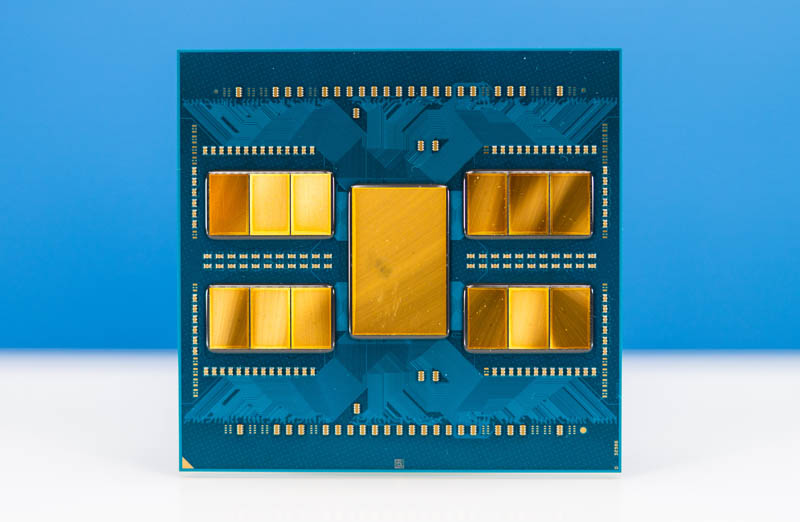

As always, we suggest watching this in its own browser, tab, or app for the best viewing experience. AMD also sent a processor shown. We need to say AMD is sponsoring as well. We also need to say that we are showing hardware from ASRock Rack and Solidigm so we need to say they are sponsoring the piece. Of course, we just get hardware and get to say what we want, but I want to be transparent here.

The Enterprise Arm Adoption Challenge

Arm has had a rough go of it in the enterprise. NVIDIA is pushing Arm CPUs in AI applications as part of an overall strategy to build systems like IBM mainframes selling the entire stack. In IoT Arm does very well. Outside of that, enterprise Arm adoption is relatively low when it comes to mainstream servers. There are a number of reasons for that, and they are very different from hyper-scalers.

In the enterprise, Arm still lacks key features to drive adoption:

- Installed base compatibility

- Hardware availability

- Feature parity with cloud options

- Software support

- License support

Installed Base Compatibility

Starting with these in turn, let us get to the installed base. It is no secret that enterprises largely run x86 compute clusters. In fact, if you were to look at the installed base, most servers out there are running Intel Xeon. AMD EPYC will likely overtake Intel Xeon on key metrics between 2025-2027 but from an installed base perspective, Xeon is still king and will be for several years.

When it comes to installed base compatibility, this is a huge deal in 2025. We will get into this in a bit, but the ability to not have to think about compatibility is great. Much of the Arm server push these days looks like unlicensed cloud-native applications, that one can convert to Arm. I usually use the example of a nginx web server here. If you are hosting in containers, not virtual machines, then the migration is actually not that bad. Or perhaps a better way to put it, the more time you spend architecting applications to be architecture agnostic, the easier it is to adopt Arm as a portion of your installed base. That, of course, requires effort in environments that are already running x86 servers so the question is why would one want to expend that effort? This is especially the case when the end result is having to run two different architectures.

Years ago, there was a push for Arm servers on power efficiency grounds over Intel Xeon, especially as Intel lost its manufacturing edge to TSMC. AMD EPYC’s use of the same leading-edge TSMC manufacturing technology limits the amount of power gains one can get by switching to Arm. One has to remember that in modern CPUs the majority of die area is not the compute cores that are different between vendors. Aside from the relatively small power gains, the challenge is that the context of those power gains is becoming a rounding error. If you save 10-50W on a mainstream 1-1.2kW x86 compute server, is that a big gain if the x86 compute server performs better?

Then in the context of AI GPU compute servers that are now well over 10kW, something else entirely has happened. Given how close AMD EPYC is on the power consumption front, and to be fair even Intel with its E-cores, something else has happened. Any power consumption gains from saving on the CPU compute side are dwarfed by the emerging AI power consumption needs. An AMD Instinct MI325X like the ones we are reviewing, has a 1kW per accelerator power consumption limit, but then has additional cooling demands beyond that. Or in other words, the story of saving power on compute by switching to Arm (or even E-cores in general) has fallen flat as switching to efficient architectures to run web servers means that you get one 8-GPU server installed for every 8-12 racks of 2U compute servers that are transitioned to different architectures.

Today, effort is being applied to wrangling AI demand. In the context of converting so many servers to more efficient optimized Arm/ E-cores to add power for one GPU server, it does not make sense to break with the installed base. In essence, the biggest reason to break with the installed base, power consumption, has been nullified by the x86 vendors becoming more efficient, then the delta becoming a rounding error in today’s hot topic of the AI build-out. We have covered this before, but a somewhat humorous version of this is that the idea of the Intel E-core to reduce the scope of application competency for Intel’s cores to get lower Arm-like power consumption ended up falling fairly flat in 2024/2025 as the industry stopped quibbling over small power consumption gains in traditional data centers.

Hardware Availability

Even if you were excited about the prospect of saving a rounding error in the context of AI worth of power consumption, deploying Arm servers, then even turning that vision into reality is a challenge.

Currently, you have the option for NVIDIA Grace servers from almost every vendor. These are limited to 144 cores in the dual CPU modules and one has to pick between lower capacity fixed memory with higher bandwidth or higher capacity fixed memory with lower bandwidth. Most major vendors will sell you NVIDIA Arm solutions, but NVIDIA is not focused on supporting them currently in the enterprise for general purpose workloads. Also, on a per-node basis, you are better off getting higher-core count Intel or AMD solutions in the vast majority of cases as the NVIDIA Grace Arm Neoverse V2 cores are starting to get very old.

Outside of getting an older architecture Grace CPU that is not designed for general purpose workloads, it is slim pickings for enterprises getting modern Arm CPUs. AmpereOne is probably the best option out there, but try finding a server from Dell, Lenovo, or HPE and that is a difficult task. Even harder is not just finding the hardware, but will your sales rep prioritize selling an AmpereOne server? Most likely not. From a top server provider, really the only options are from Supermicro like the Supermicro MegaDC ARS-211M-NR we reviewed. Still, if you wanted different form factors CPU configurations and so forth, you are still stuck.

I should mention there is the HPE ProLiant RL300 Gen11 that we reviewed. That used the older DDR4 generation Ampere Altra (Max) processors and was a single-socket only platform. It was a perfectly acceptable HPE ProLiant server, but largely failed in the market. The reason for this was that it was hard to get folks around the installed base incompatibility and the lack of breadth of options (e.g. a dual socket ProLiant Arm server.) That combined with an earlier generation Arm processor, and it was not successful.

From an enterprise standpoint, usually there is a primary IT vendor relationship and if that vendor does not have Arm, then it is simply a no-go before the project even starts.

While software is key, it’s an interesting observation that current ARM hardware is not attractive enough to motivate further software development.

ARM had its chance when the Raspberry Pi craze put a small ARM development system on every software engineer’s shelf while Fujitsu and Nvidia started building systems with competitive performance. Unfortunately Nvidia’s bid to take over ARM with a well capitalised development team was rejected on political grounds, AmpereOne underperformed, the Raspberry Pi craze faded and ARM sued Qualcomm for breach of license. Given how ARM intellectual property appears impossible to sell, the only recourse was for SoftBank to purchase Ampere. The above chaos suggests an uncertain future and missed opportunity for ARM.

On the other hand, IBM Power has no entry level hardware, no new customers and as a result few independent developers. It’s possible OpenPower will lead to cost competitive hardware ahead of RISC-V. It’s also possible neither will succeed and Loongson with LoongArch will emerge as the next dominant architecture.

Yesterday the enterprise solution was System z, today it is x86 and tomorrow has not yet arrived.

If ARM were in the NVDA stable as obnoxious as it sounds, it would have a brighter future, forcing the software dev in the pursuit of AI. ARM has for decades chased efficiency rather than raw performance. And currently it’s close on performance, close enough it would take off if it weren’t for per-core pricing and migration headaches between architectures. The answer from ARM’s stable should be – extension of the arch for performance gains. That – means bigger silicon, losing the efficiency that got it in mobile splitting the designs between mobile and power.

LoongArch/Loongson would have an even larger up-hill battle in the enterprise for adoption even more so in the ‘west’, having all the caveates of ARM, and RISCV but also the fallout of political/tariff issues as well. Apple’s ARM arch will continue to be the prime competitor from an architectural standpoint. Compiler builds per arch probably, pits Apple ARM M chips vs x86, nothing else comes close today.

I really like RISCV but it’s open nature will mean fragmentation of designs. I don’t think it would be adopted server-side any better than ARM and probably worse.

Also, RPi’s are everywhere still, and I don’t think they are moving to RISCV anytime soon.

I think most arguments are not relevant. Regarding software, the Linux stack with its open software in the distribution’s repository overwelmingly runs on ARM, which covers the most common server use cases.

Things like nested virtualization, proprietry software (Oracle, etc.) exist but today are not comprising the majority of use cases.

My argument is that the thing that matters most is total cost per performance unit. On AWS, ARM is slowly eating into the marketshare, currently at 25% of total and rising.

I don’t see this trend changing anytime soon, and other hyperscalers will follow. people/companies self-hosting/colo-hosting these days are not early adopters and will follow over time.

WTF do you need all that computing muscle for ?

Do you have a massive operation and STH is just hobby for you guys or what ?

@Patrick Do you have any idea why there are no Tower Servers with EPYCs from any of the major OEMs? (Dell, Lenovo, HPe)? The Tower server market is a bit niche but it’s also a very useful option when you don’t have dedicated server rooms or cabinets. Unfortunately, all of these options are intel-Only. Any ideas?

That’s AWS. They’re discounting to lock companies into their cloud. If you’re running enterprise IT you’re running on x86 today b/c you’ve got many apps that don’t run on Arm. Outside of AI spend, the hip thing to do today is to move off of cloud into colo. Companies that are still cloud only are weak IT departments that don’t have the skills to do it themselves because they’ve got weak CIOs. I work at a large F500 company, and our ROI for moving workload off the public cloud was under 7 quarters. The workloads we moved off were the result of a trend following our previous CIO who wanted to sound like they were doing something on trend, but they were just putting IT on autopilot without adding skills to our team.

Public cloud is great if you need burst, or if you need so fast you can’t do it yourself yet. If you can, then it isn’t just about the instance pricing and it’s a lot more expensive once they’ve gotten you locked into their platform.

I have over 200 people working for me. If one of them stood by, we need to add Graviton because it’s cool, I’d coach them to find a new job.

For enterprise IT with established on-premise datacenters, hybrid cloud (whatever that means) is the sensible approach. For me hybrid cloud implies the same or similar infrastructure in the cloud is also available locally and provides flexible resilience as well as a lever when negotiating both on and off premise prices.

As discussed in the article, ARM is not great for hybrid cloud strategy because on-premise Altra and AmpereOne servers are slower than Amazon Graviton and Microsoft Cobalt. As also mentioned, since it’s difficult to migrate valuable legacy software to ARM an enterprise with existing datacenters ends up with a long-term combination of x86 and ARM systems–yuck.

For IBM shops the problem is reversed. Hybrid cloud is difficult because the major cloud providers–Amazon, Azure and Oracle–do not provide Power and System z instances. Given Amazon’s attempt to capture HPC and AI workloads, I’m somewhat surprised they haven’t sought traditional IBM workloads.

I also wonder what Serve the Home does with all their servers when not evaluating them for a journalistic review. Practical use provides important insight and that’s what this article is about.

While likely just a brainstorm, an independent test bed available for companies to compare competing hardware would be really useful and Serve the Home has the stuff to do that. It’s another level to securely give people access to run their own tests, but doing so would illustrate additional aspects the review hardware.

> “… there really is no legitimate way to download an instance image and turn it on in a server that you bought from a major vendor on prem. … but performance varies to the point that you might have to spend time analyzing that.”.

Easy to say: Just use “dd”, VMWare migration, or Hashicorp Packer. Slightly harder to do: Practice makes perfect. It’s not just the CPU (and this applies to x86 too), they’ve got the connectivity (and bigger pipes), more hardware in many cities to failover to (which you can do from the home or office; but monthly fee), and people 24 hours, and you can reconfigure or move quickly and scale-up huge for an event – all things difficult to do from the office.

It’s never one thing, one thing is the best. It’s frequently several things all work together extremely well, maybe almost perfectly, even if a few of those things aren’t the ‘best’ (and x86 isn’t far from it for most people), it’s that all the things just work; there’s no tripping point or wall or unexpected goal post movement.

@Vincent S. Cojot: The Lenovo ST45 V3 Tower Server features the AMD EPYC 4000 series CPU’s. As you call out, the tower form factor is ideally suited for deployments where you don’t have dedicated server room or cabinet. It is a compact tower and currently supports up to 12 cores (16 cores that can optimize Windows Server licensing coming soon)