If you look at any major server CPU launch, you will undoubtedly see some form of claim that the CPU is good for databases. Storing and retrieving information is a basic function of traditional computing. Recently, I was at a dinner with a number of STH readers, and all of them ran databases. One individual exclaimed how they had nightmares of a 192-core processor, while another was explaining how awesome that would be to deploy. Funnily enough, both were talking about databases as applications that led to those feelings. As a result, I thought it was worth doing a less review-oriented piece and instead talking about some of the big database areas that drive performance and cost.

As a quick note, since I wanted to talk about cache, cores, and other features, we are going to use AMD EPYC CPUs. AMD sent the CPUs for the previous pieces on STH. We need to say this is sponsored.

What is a Database Anyway?

This is a question most folks know the answer to, but I have learned many have a specific type of database in mind. When they talk about database performance. The classic relational database runs enterprises, websites, and many applications we use daily. NoSQL databases for scale-out, in-memory databases, graph databases, time series databases, vector databases, and more all underpin enterprises, cloud services, and even SMB applications. People store lots of different data types, and want to organize and later access it in different ways.

Some databases, especially relational databases are designed to scale up usually in a node, as are others like in-memory databases. Other databases like NoSQL databases are designed to scale out.

At its simplest form, however, databases have a few common traits. For example, they all store data, have some form of organizaton for that data, and then have some way to access that data later using the organization to help retrieval.

That leads us to some common attributes that tend to influence all database performance. Usually, there is storage performance, since the goal is to store data. Then we have compute performance since once we have data we want to do something. Memory heirarchy performance is also very important since we need to keep compute resources filled with data to use that compute power. Depending on how the data is distributed and where it is stored, networking can also play a role.

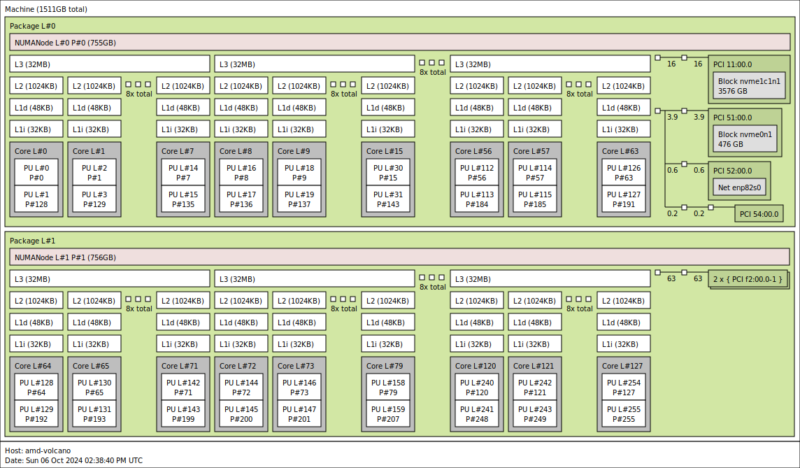

Perhaps the reason server CPUs tend to be so important with databases is because they are the hub. Oftentimes, CPUs are the main compute resources. The memory capacity and performance often is directly impacted by the CPU from the on-package levels of caching to the off-package memory interfaces. Whether the storage is local or over the network, and for distributing work across many nodes, PCIe performance is important as well, and PCIe devices generally plug into CPUs in servers. Another way to look at it is having lots of compute, cache, memory, storage, and networking is generally ideal.

At this point, you are probably thinking that a pair of 192 core AMD EPYC 9965 CPUs with 12-channels of DDR5-6400 and plenty of PCIe Gen5 connectivity is perfect, as did one of our readers at this dinner. There is, however, more that goes into a database processor selection, and a big one is licensing.

2025 Database Licensing Guides Decisions

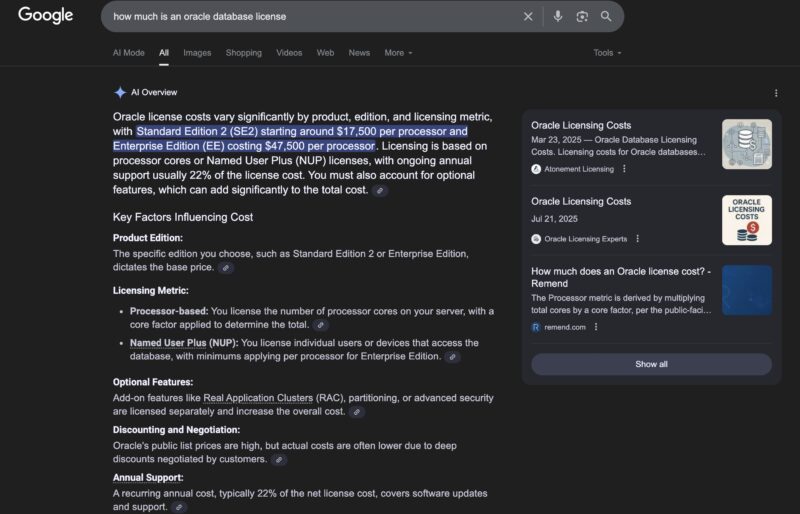

Database licensing is often tied to an array of factors. High-end enterprise relational databases that are running Fortune 500 ERP systems, or other critical applications generally come with very high license costs along with support contracts. Oftentimes, there are lower-cost versions missing a few very high-end features but at significantly lower costs for mid-sized enterprises. A great example of this is for Oracle Database licensing. One is not supposed to reproduce the official Oracle Price List, however thanks to Google Gemini AI, search snippets now give us a good answer to the question of how much a license costs.

Also noted in the snippet is that figures like $47,500 does not take into account that CPUs like the AMD EPYC and Intel Xeon processors currently use a multiplier of 0.5 to calculate the number of cores. There are optional features, different versions, annual support, and more that can modify the list price. Then, as is typical in enterprise hardware and software, there is usually significant discounting that brings the cost from a list price to a deal price.

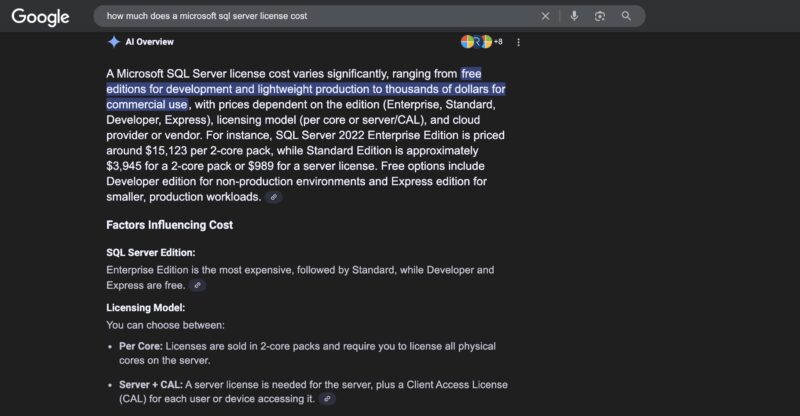

Oracle Database is just one example. Microsoft SQL Server is another extremely popular database, so to be fair, here is the AI Overview for that as well with the $15,123 per 2-core pack. Here is the Microsoft SQL Server 2022 licensing page with a FAQ on how to navigate it.

While those are focused on per-core costs, there are other models such as per node, or even per GB of memory installed in systems. One great example might be SAP HANA:

We commonly see SAP HANA mentioned during launches. The pricing is tailored to the application since as an in-memory database simply having a lot of memory capacity is desierable.

There are other common databases out there such as PostgreSQL, MySQL Community Edition, Redis Open Source, and more that are extremely common due to their free versions. These are important cloud-native workloads and run large portions of the Internet. They often have support or other upsell features for those who require it.

While traditional relational databases and SQL that hold transaction data might be very different than vector databases indexing photos and video with embedding models and vector indexing in terms of how they work, one thing every organization cares about is how much the database costs. Since so many databases are licensed (and supported) with per-core or per node driving the cost, server CPUs are a primary lever one can use to control costs of databases. As you may be able to tell from the above cost examples, a CPU that costs single digit thousands of dollars is often a small cost for running the application, but one the selection can have an enormous impact on costs.

Against that context, let us next get into how folks pick server CPUs to control database costs.

I specify a lot of db servers and it’s really not rocket science. For licensed rdbms you want as few, fast cores as possible. Multiply cores x speed to compare. You can save a lot of licensing cost for SQL Server (if you have a good number of vm’s) to throw them all on a virtualisation cluster and license the physical hosts for SQL Server enterprise edition. For Oracle, Exadata machines really aren’t bad value.

Just switch to open source dbs, problem solved

It’s not too complex.

If you must run specific software then you’ll want just enough hardware to service immediate and near future needs, to save a fortune on licensing costs. Otherwise (as Pierre pointed out) run open source, but try to ensure that there’s excellent community support and that there’s paid support available (such as is available from some companies who release a full version publically, and solely make money off it by both offering paid support and accepting some community submissions of code).

With that software model you want maximum L3, high frequency and many cores on two processors, possibly going with half the maximum number of cores; that saves money for memory, cooling costs, and might allow you to sit in a SKU notch where maximal L3 and frequency hide (as they’re just not available on a full out maximum core system).

As long as you aren’t painted into a corner with an expensive upgrade path you’re all set.

Don’t forget, AT and HFT have databases too; and need FPGA SmartNICs. Make sure you have budget for additional hardware and PCIe lanes to access it (thus, 2 CPUs. Both for lower cost memory and more lanes, along with some redundancy).

Short of having to satisfy some unusual functional or compliance requirements – best open source database (which is workload specific) + modern hardware wins every time on a price/performance basis (often by a very large margin due to absurdly expensive proprietary license cost per CPU core).

I think the main reason IBM Power uses eight-way SMT per core is cost optimisation of common but otherwise arbitrary per-core software licensing. Since hardware constraints come from physics, I find it surprising that licensing policies are able to contort hardware in such substantial ways.

Good but you can talk about databases without mentioning MariDB /MySql, the most popular database in the world.

I’m mostly working with Postgres and sometimes MariaDB, I do have a customers who run proprietary database like MS-SQL or Oracle – where this gets complicated is that legacy applications often run a lot of code in the database which makes it more CPU intensive.

One consideration with any database would also be how much of the dataset you are accessing regularly and how much of it is kept in memory. It can be beneficial to have a single CPU server instead of two sockets to avoid issues with NUMA and then you also want to look into optimizing memory bandwidth per-core. Most of what database software does is just copy data around and perhaps do simple calculations so you often see idle CPUs waiting for memory or flash. Better to prefer fewer P-Cores with higher speed over lots of small cores. Additionally it’s often not possible to serve a single query with multiple cores at the same time.

Our SQL database is running heavy SSIS to extract and transform data from the source. We are seeing huge performance improvement moving from 32-core Zen2 to 9375F (Zen5), and are now considering reducing the core license in the next renewal.

We are also seeing a 2x improvement when moving (vMotion) from 32-Core Zen3 to 9375F for our Qlik Sense server, which is running on VMware. The higher frequency, larger L3 per core, and larger memory bandwidth really shine.

We routinely cut cores on large DB-focused instance types in AWS to meet our licensing restrictions for SQL. The drawback is you paid for cores you didn’t use but you typically get much higher ratio of RAM to Cores, and SQL loves more RAM.