If you are reading STH, there is a great chance that you have seen DDR5 pricing in the consumer market has spiked. For many segments, DDR5 pricing is going up as AI data centers are putting significant demand pressure on the DRAM supply. As a result, hyper-scalers are turning to the tens of Zettabytes of DDR4 they have purchased over the years to lower the impact. We went to Marvell to see its Structera X CXL Expansion in action. While we were there, we also got to see the Marvell Structera A that combines 16 Arm cores with the DDR5 CXL controller, so system builders can scale both compute and memory. There is a narrative that CXL is not suitable for AI, but we have a great example of how CXL memory can increase performance.

Note, we flew to Marvell’s labs to film this video, and got special access so we have to say this is sponsored.

Marvell Structera X DDR4 and DDR5 Controllers

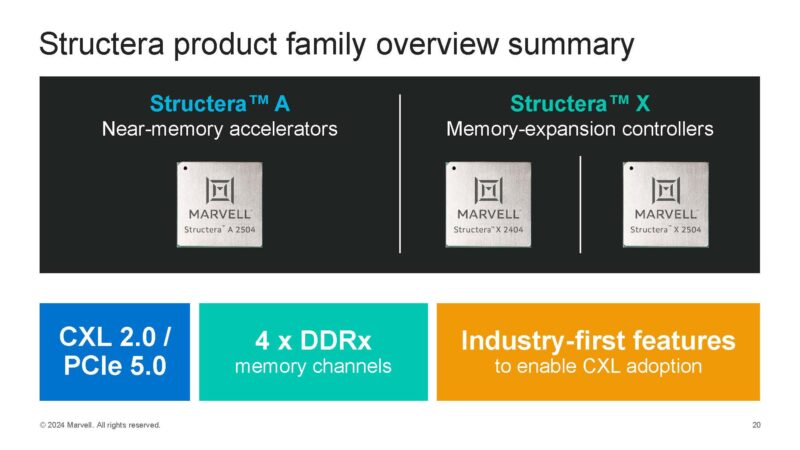

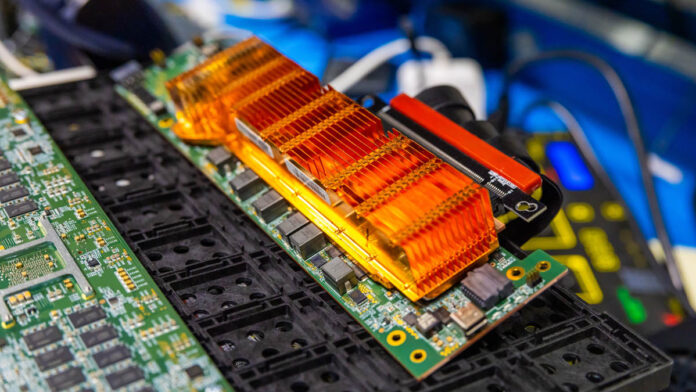

While we were at Marvell, we got to see all three Structera chips. That includes the Structera X, which are memory expansion controllers, and then Structera A, which adds memory expansion, plus sixteen Arm Neoverse V2 cores. These are the high-performance Arm cores, and we always wondered how they worked. Not only did we see that, but we saw some examples of how “slow” CXL devices actually can speed up systems.

One huge feature in these is that the CXL devices also support LZ4 compression at line rate of the memory. Marvell told us that it has been seeing 1.8x to 2x compression ratio. Let that sink in. Not only can you add memory, but if you add it on the Structera controller, your effective cost per GB is roughly half versus if you were to install it elsewhere.

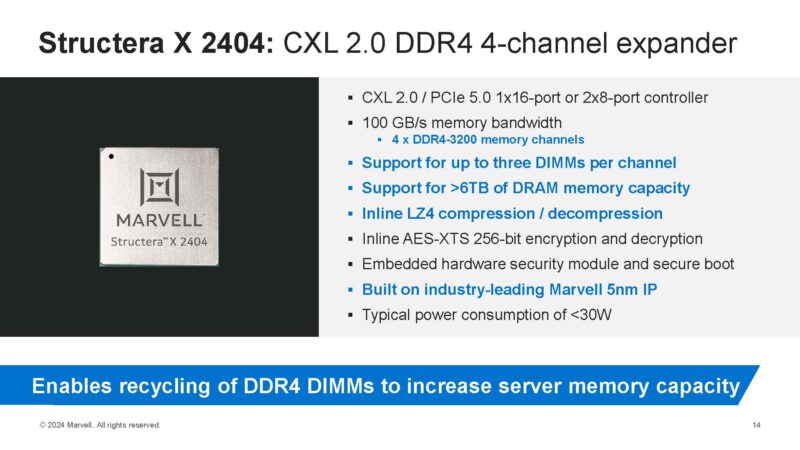

Starting with the Structera X 2404, this is a DDR4 expander with 4-channels.

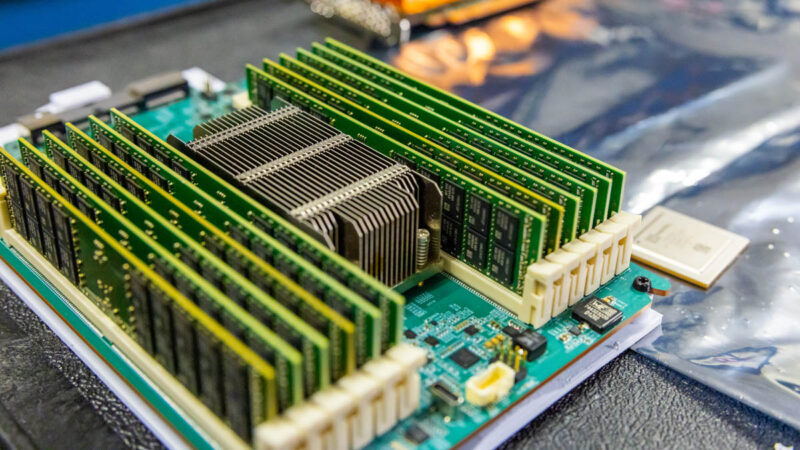

For hyper-scalers, this is something that is extremely attractive because you get not only four DDR4 channels, but you can do three DIMMs per channel or 3DPC. In other words, you get twelve DDR4 DIMMs per Structera X controller.

If a hyper-scaler pulls 128GB DDR4 DIMMs from decommissioned servers, effectively making them “free” it can then have 1.5TB of memory on a single Structera X 2404 controller. With compresison that is roughly 2.75-3TB of effective capacity.

Another benefit to this model is that the hyper-scaler gets to recycle the memory meaning that to deploy this the only manufacturing that needs to happen is the cable, board, and the controller, but not the DRAM. For those with environmental impact targets (let us forget AI for a moment) the impact of this goes beyond just the cost savings.

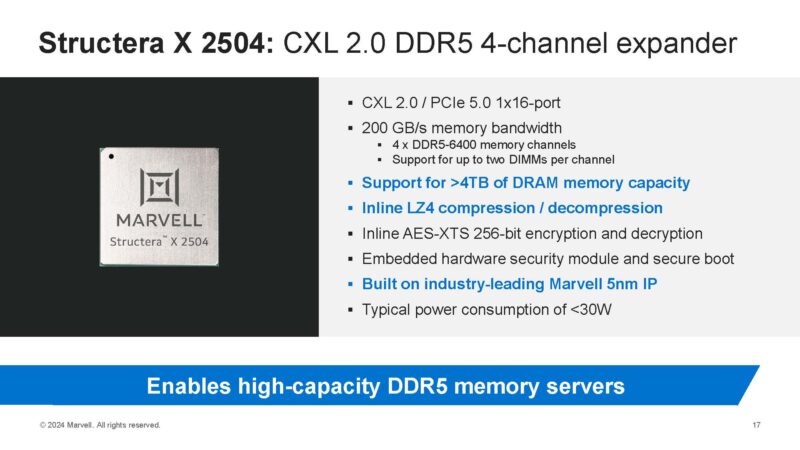

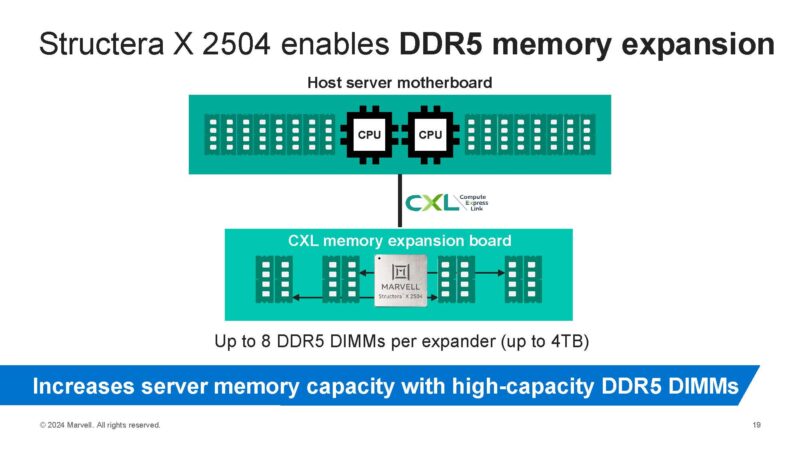

The DDR4 version is more of a cost play, but one pays for that cost in performance since you have much lower operating speeds. For those who want CXL memory epxanders with higher performance, there is a DDR5 4-channel version called the Structera X 2504.

This also offers LZ4 compression, meaning that not only can you add more memory to a system, but the memory you add to this is effectively less costly than if you add it to a CPU’s DDR5 DIMM slots because you get more capacity per dollar.

The other benefit is that you get more bandwidth since CXL goes over the controllers and wires for PCIe not the DDR5 controllers and wires. As a result, this net increases both the memory capacity, but also the available memory bandwidth in a system.

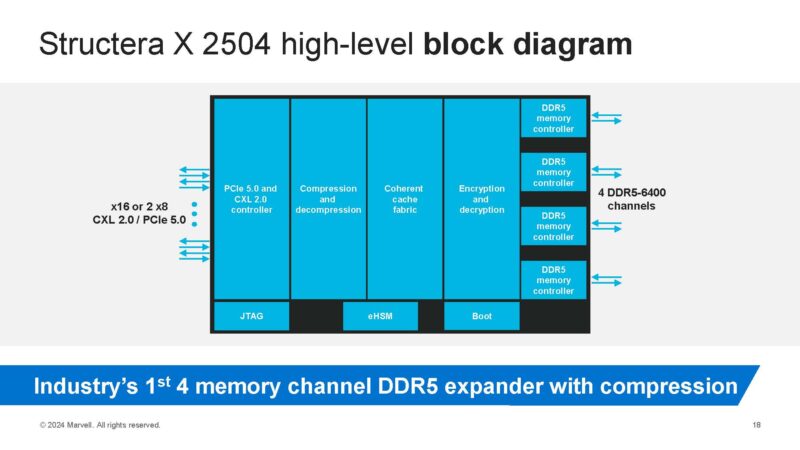

If you were wondering how Marvell is doing this, think of a CXL controller using this block diagram. One side connectx to the CXL 2.0 / PCIe Gen5 lanes. The controller has the compression and decompression/ encryption decryption IP. It then has the memory controllers. These memory controllers in the DDR5 version are DDR5, and in the DDR4 version they can be DDR4. In theory, with CXL you can use different types of memory.

All of this is great, but it was time to look at the hot rod Structera A with 16 Arm Neoverse V2 cores built-in, and then get them running.

Without third-party testing of latency, bandwidth and latency while being bandwidth bottlenecked it’s difficult to know whether this is useful or not.

I’m curious how the additional uncertainty introduced by memory compression is handled. A lot of real world data is amenable to lossless compression; but not all to the same degree and some not at all.

Is the compression visible to the OS and its memory allocation mechanism; with that responsible for deciding how much compression to expect and how to respond if that expectation proves optimistic and there isn’t as much physical RAM as required? Is it invisible to the OS and the CXL device presents itself as larger than the physical RAM with a margin of safety chosen to make hitting enough incompressible data to run out unlikely?

After reading this article, I instantly became bloated with an unbearable amount of gas buildup leading to an unequivocal paradox of methane emissions. This has lead to fecal aerosol toxicity levels of astronomical proportions in my proximity.

With composeable infrastructure, being able to add 10s of TBs of RAM with a server or two is pretty cool.

Latency. Latency. Latency.

How about we agree that it’s illegal to publish any future CXL article without measuring random read latency? Concurrency would be nice too, but please don’t bother with the easy one, bandwidth.

@Eric Olson – It’s really not difficult for most use cases. If you’re memory contrained and spilling to flash/disk then it will 100% be a win. How much of a win, that’ll take testing. But it’s likely significant.

What I find puzzling is the A model. Unless they built it for a particular customer and are testing the waters to see if there are any other takers. It’s a very heavyweight PIM/PNM- in fact it’s a lot more like building a cluster of small nodes using ~400gbps connectivity.

Taking advantage of this will require lots of custom code/tooling for most use cases (other than those that are extremely parallel and rightsized for these nodes). For any cases where the nodes all need a bunch of disk I/O, it’s likely to be utterly inappropriate (unless they have a correspondingly low need for network I/O, at the very least).

@Eric Olson

If you are using something like ESXi there is already a lot of “RAM” that is just page file on the SAN. From an end user perspective you don’t notice this at all and that latency and bandwidth is already less than even DDR4 CXL. These are running on a PCIe 5.0 x16 connection which is 512Gb/sec (64GB/sec) connection, much faster than even a 200Gb/sec SAN connection and with far lower latency.

I doubt this will help from everything iv read the Ai tech bros as never satisfied they are taking all HBM all dram all Vram they can get to the point Micron said FU to consumer’s so they can focus only on the Ai tech Bros.

Tech demo, never a real at-scale usage. Noone will use DDR4 from decom servers. Have fun with the failure rates after 5-6 years. Nope. And that’s disregarding the different latencies for non-CXL aware applications.

Basically, everything inside a computer is becoming a mini-computer powered by ARM. I can already see a future where an SSD has a 32-core ARM processor, NICs have their own GPU units, and with CXL merging with RAM, a central processing unit (CPU) might not even be necessary. It would be perfectly scalable: if you want to run a business application on a server, you just plug in a new SSD where the application itself lives (with data stored elsewhere, this would be raw application power) without slowing down the rest of the system.