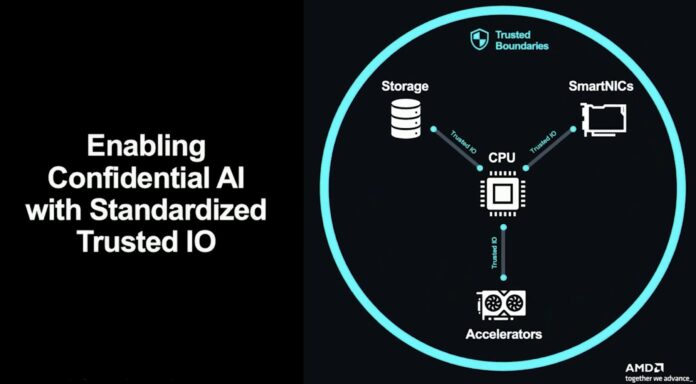

Confidential computing is a term you may have heard in the past, but it is also one that a lot of the industry is sleeping on. Many cloud providers are looking towards a world in the not-too-distant future where confidential computing is ubiquitous. While it is challenging to secure a computing environment to ensure the data brought into that environment is safe from even a cloud provider, it is even more challenging to expand that past the CPU motherboard and to AI and other accelerators. As such, it was time to get into confidential computing.

As a quick note: Confidential computing is an industry-wide effort, and needs to be. At the same time, we cannot go into every unique implementation of it, so instead, we are going to use AMD SEV-SNP for our examples since AMD is already powering many of the confidential computing cloud offerings and they are rapidly growing server CPU market share. We need to say AMD is sponsoring this.

Confidential Computing: Protecting Data in Use

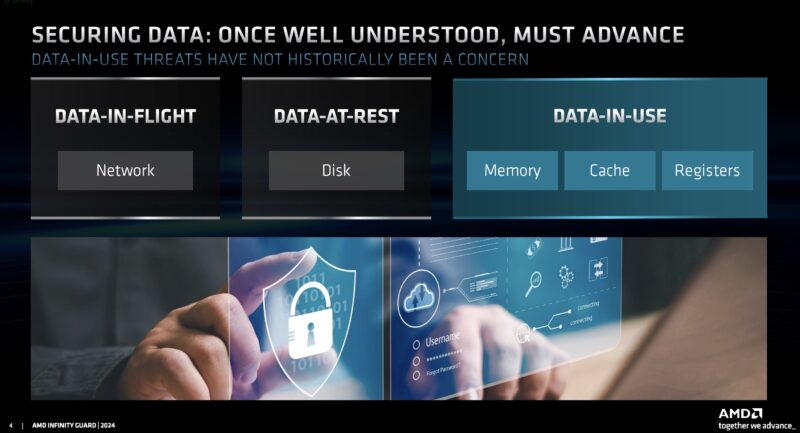

When it comes to data security, most of us have been trained to think in two dimensions. We protect “data at rest” by encrypting it where it is stored. This can be on self-encrypting SSDs, in encrypted storage arrays, or encrypted by the application.

We protect “data in transit” by encrypting it between two endpoints. These days, virtually every website uses HTTPS. Inside large data centers, even network flows between machines are often encrypted as default behavior.

Those two models are in many ways the easiest to accomplish, but they leave one big vulnerability, data while it is being processed and used by an application. If you take your data from storage and then want to use it, then it is usually decrypted and copies are stored in RAM and caches of a server. This in the industry is called “data in use” and traditionally, when being used data is completely vulnerable.

In the video, we illustrated this with play money as a proxy for data (since data is a valuable asset). Data at rest would be like putting it in a safe while you are not using it. Data in transit would be like taking the money (data) and putting it into an armored truck so that it is not intercepted in transit. Data in use is like taking all of that money, putting it on a table at a coffee shop, and leaving it sitting there while you pay for your coffee.

As an industry, folks realized that they needed a solution, especially for industries with strict confidentiality and sensitive data. Better put, after data at rest and data in transit became standardized, the next step was the hard one. That step is figuring out how to secure data that needs to be decrypted for processing while it is being decrypted.

Enter the TEE

Fundamental to confidential computing is the TEE or Trusted Execution Environment. The idea behind the Trusted Execution Environment is to create a virtual machine environment where the customer of that environment knows that it is secure and has not been tampered with, before bringing data to be processed there. Maybe in our example above, this would be like storing your money (data) in a bank so that it could be used in the banking system without directly exposing it to passers-by who want to pilfer funds.

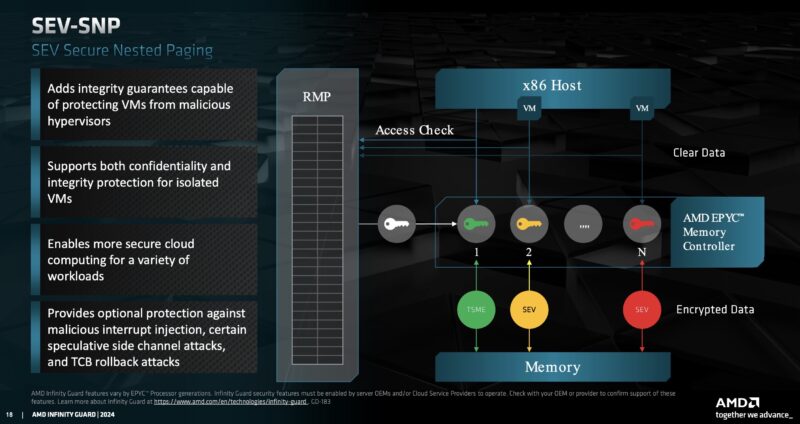

AMD has its Secure Encrypted Virtualization (SEV) and the newer SEV-Secure Nested Paging (SEV-SNP) features. Intel originally thought Software Guard Extensions (SGX) was going to be the answer. That created enclaves for applications to use with sensitive data. The challenge was that it required software changes. Folks did not want to pivot the software they were running on to get confidential computing, so Intel now has its newer Trust Domain Extensions (TDX), which align more with industry principles. Arm has its Confidential Compute Architecture (CCA), which creates “Realms” as its secure enclaves.

This hardware-based TEE creates a secure enclave to protect both the code and the data inside it. When we say protect, that is not just from other virtual machines that may be running on the same system. Even the hypervisor and cloud provider are locked out. Getting to a TEE is not automatic.

That is where remote attestation becomes important.

I wonder how much resources sacrificed (silicon, power, efficiency and headache for programmers) to ensure secure encryption for all computer parts. While still having really fast compute capabilities.

Compare to old way computing that try squeeze every cycle just to make compute more faster.

That’s how much progress we already had in half century.

Starting with Spectre and Meltdown it became clear to non-technical people that there are technical reasons why cloud vendors can not securely provide virtual machines to adversarial renters using multi-tenant hardware. From what I can tell, the clouds are too well established to give up on such a profitable scheme.

On the other hand, if you can get the job done with the overhead needed for secure cloud computing, it’s likely the problem you are solving is trivial relative to modern technologies. Creating useful AI is not currently a trivial problem that can afford the extra overhead. This is because smarter chatbots are universal more useful than stupid ones and they’re all pretty stupid right now.

From a different point of view hardware that prevents cloud vendors from snooping on their customers could be important to protect those vendors from legal complications related to search warrants and criminal activities.

In my opinion there are lots of advantages with a competitive free market for computing hardware that supports the construction of cost-effective on-premise datacenters.

No, it doesn’t.

It still has way more fundamental problems to solve.

Like finally having a decent RAM that is actually immune to FRIGGIN ROWHAMMER attacks.

Or architecture that has definitely solved timing attack holes – whole concept of virtualized CPU core is flawed as it turns out.

But why do that when advertisers have next shiny thing to sell, even though the last ones have been proved defective, right ?

When someone with time to spare finds a shocking hole in SEV, it’s time to sell a new version, right ?

Marx Brothers economy…

Memory encryption (which is required but not sufficient for SEV) does actually help with rowhammer as you cant target the raw bit patterns any more once memory is encrypted.

Developers won’t refactor apps for confidential computing until it’s seamlessly available everywhere, and cloud providers won’t prioritize seamless integration until there’s proven demand. The performance overhead, while decreasing, is still a real tax.

My question is about the path to the “mainstream” tipping point:

Is it more likely to be driven from the top down by a regulatory hammer (e.g., a future GDPR amendment explicitly requiring data-in-use protection for certain classes of PII), or from the bottom up by a killer use case?

That use case might not be just “secure financial transactions.” Could it be the enabling technology for a cross-industry, privacy-preserving data consortium? For example, multiple competing hospitals confidentially pooling patient data in a single enclave to train a diagnostic AI model none could build alone—where the raw data is never exposed, even to the cloud provider. Once that model proves its value, the dam might break.

The technology is maturing, but the ecosystem needs that compelling, undeniable business reason to justify the refactor.

I really wish that ServeTheHome would have a SPONCON tag for all sponsored articles, rather than a throwaway sentence mentioning that it is sponsored.

Also the analogy proposed is incorrect:

“Data in use is like taking all of that money, putting it on a table at a coffee shop, and leaving it sitting there while you pay for your coffee.”

No. Data in use is like taking the play money out and placing it on the counter when paying for your coffee. I.e. In use. Not leaving it on a random tabletop that is not involved in the transaction.

There are some banking regulations (DORA) that now require data-in-use encryption, of course this is a bit silly since you need to access the plain-text if you’re using the data but such pedestrian concerns never stop the regulators.

Of course there is a massive issue where pretty much all transport and at-rest encryption that uses public cloud infrastructure or CDNs requires the provider to hold the keys so there is always a third party that has access, can be compromised or compelled to disclose data.

I don’t know if you’ve meant to in a piece that’s “AMD sponsored”, but you’ve created the best confidential computing primer on the Web. At least I’ve read about it but this is the first time I’ve come away and it clicked on how they’re doing it. We’ve been asked to do this at work next year so I was doing research for the last 3 hrs

This is a really nice explainer on CC, thank you! But as a researcher working on CC and remote attestation, I would like to add a few caveats:

1- Current implementations aren’t nearly as secure as the manufacturers claim. Attacks like ‘TEE fail’ (Chuang et al.) and BatteringRAM (De Meulemeester et al.) have completely broken them by using cheap hardware memory interposers. These could be mitigated but AMD and Intel just shrugged and said “we consider physical attacks out-of-scope”, which is not realistic if you consider the cloud provider as an adversary (which you should!). The result is that BatteringRAM can replay SEV-SNP attestations and thus makes them completely useless (it can also replay full SGX enclaves, fully breaking their encryption). ‘TEE fail’ completely breaks TDX’s attestation by leaking a signing key from Intel’s Quoting Enclave. Both of these are fixable but will require significant effort from AMD and Intel. There is some hope that RISC-V cove or arm CCA could resist these attacks but that is unclear right now.

2- The process to create the attestation report for a confidential VM is currently also not very standardized/complete. A normal confidential VM will provide you with an attestation report that includes the platform (is this actually a hardware backed environment with valid firmware) and the virtual firmware (UEFI) that’s booted (+ some metadata about the initial state of memory pages). This is far from a complete picture, it does not include the guest kernel or any of the userland. There ways of doing it by embedding a hash of the kernel into the virtual firmware or using vTPMs (using AMD’s VMPLs) but this fairly new and is far from standardized currently. Scopelliti et al. actually wrote an interesting paper analyzing different cloud providers and what kind of attestation they actually provide (title: “Understanding Trust Relationships in Cloud-Based Confidential Computing”, DOI: 10.1109/EuroSPW61312.2024.00023).

We’re working hard on improving all this and I am very excited about the future of this technology so thank you for giving it a platform!