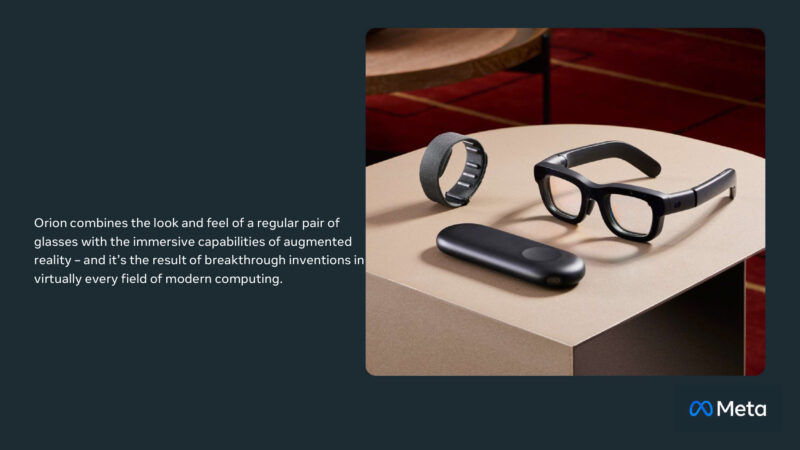

The final graphics-related talk of the day comes from Meta, who has perhaps the most novel presentation on the graphics track. Rather than talking about GPU architectures that have already been shipping to customers for several months, Meta’s ex-Oculus headset division is at the show to talk about using dedicated ICs for accelerating world-locked rendering (WRL). WRL is of particular interest to the company as part of its development of AR/VR glasses, most notably its prototype Orion glasses, which are pushing the limits of what can be done in the space and power budget of relatively small glasses.

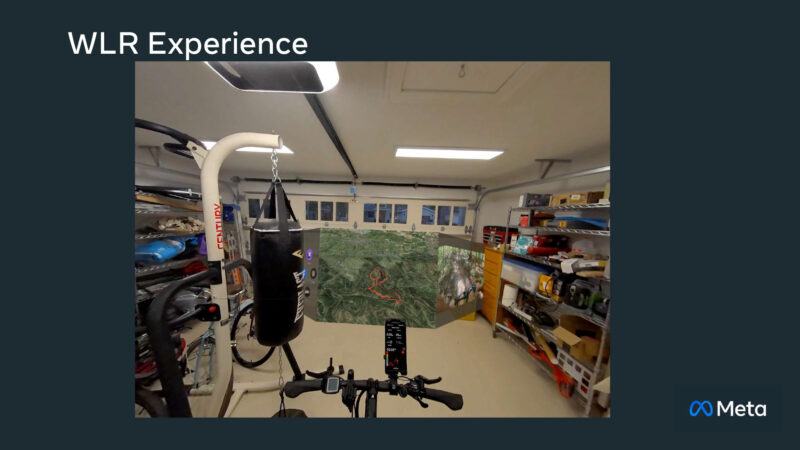

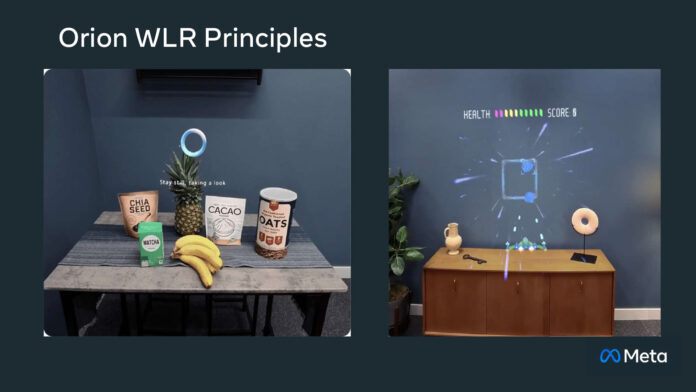

World-Lock Rendering, in short, is the technology that keeps a rendered image locked to a point the world as a user’s head moved around. It’s what keeps an image floating in front of you, but locked in reference to the rest of the world around you. This also covers things like occlusion, with real-world objects occluding virtual objects.

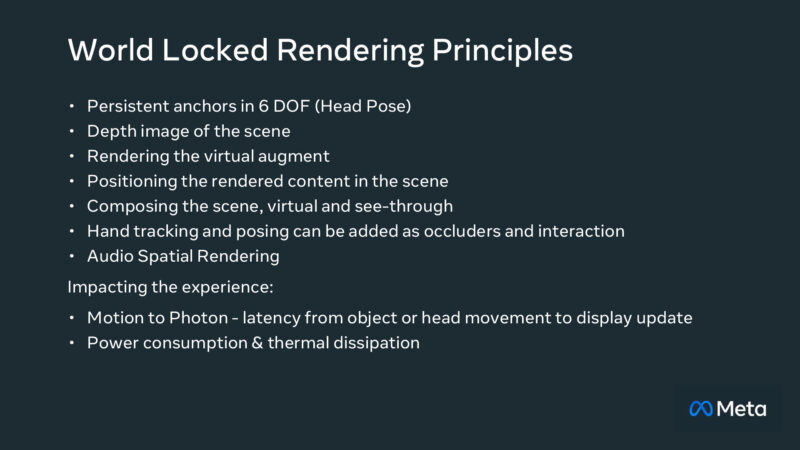

Recapping the principles of WLR: anchored objects, depth calculations, actually composing the rendered and real worlds together, and even audio spatial rendering. And these principles cover not just the steps to rendering, but the need to accomplish this very quickly, all the while consuming as little power as possible.

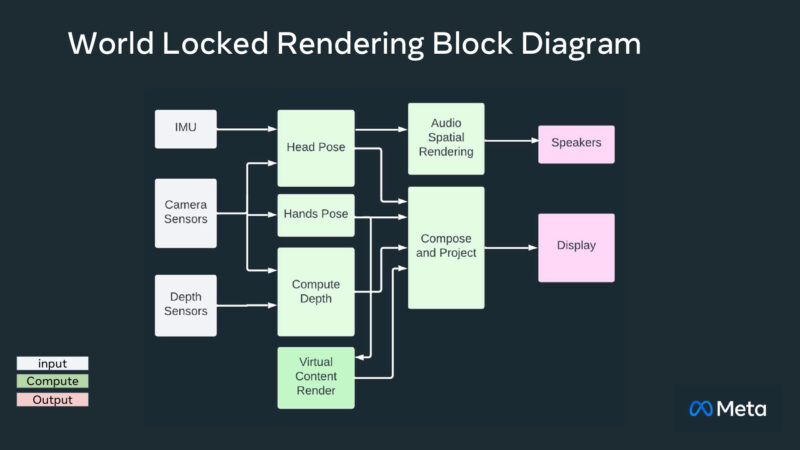

And here’s a block diagram of the basic WRL algorithm. Inputs from the inertial units and other sensors, and then several stages of compute before composition and projection.

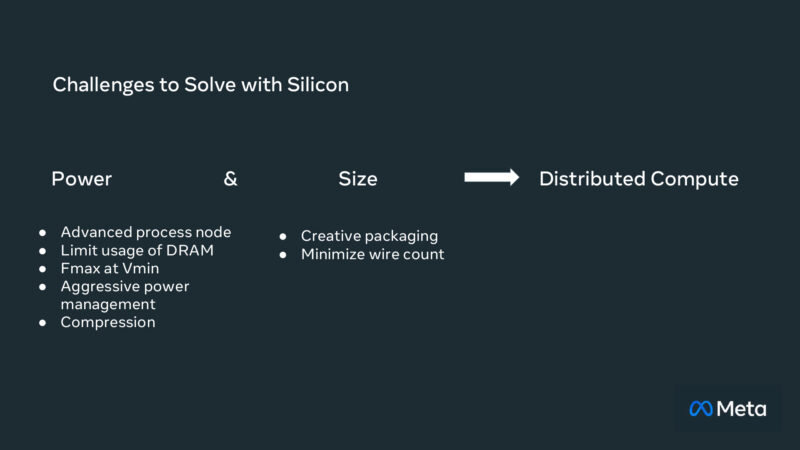

The physical constraints of the glasses mean that the power budget for WRL is extremely limited. Meta uses all of the tricks of the trade, from a cutting-edge process node (5nm at the time Orion was conceived), limited DRAM usage, compression, and extensive power management. Even then, physical size is an issue as well, since the glasses don’t leave much room for chips.

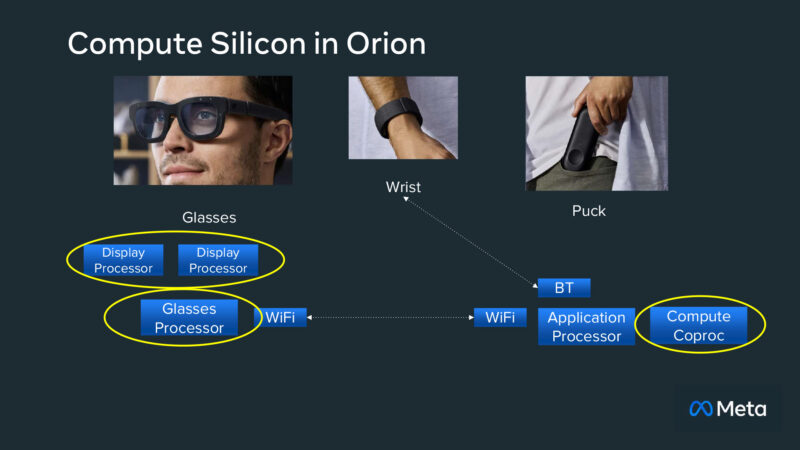

As a result, Orion splits up compute between the glasses an an external puck. WRL is extremely latency sensitive, so it needs to happen in the glasses. There are 3 major processing chips overall: display processors, a glasses processor, and a compute co-processor in the puck.

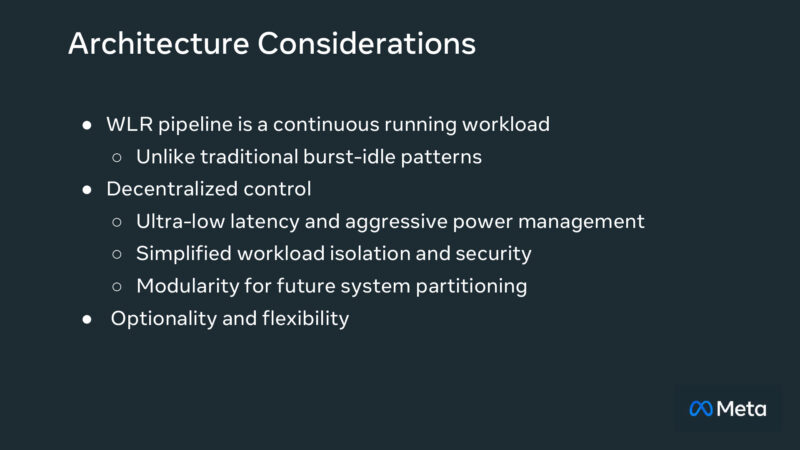

WLR is a particular workload in that it’s always running. So there’s no bursting to be had like in most traditional workloads. So its hardware needs are quite different, in certain respects.

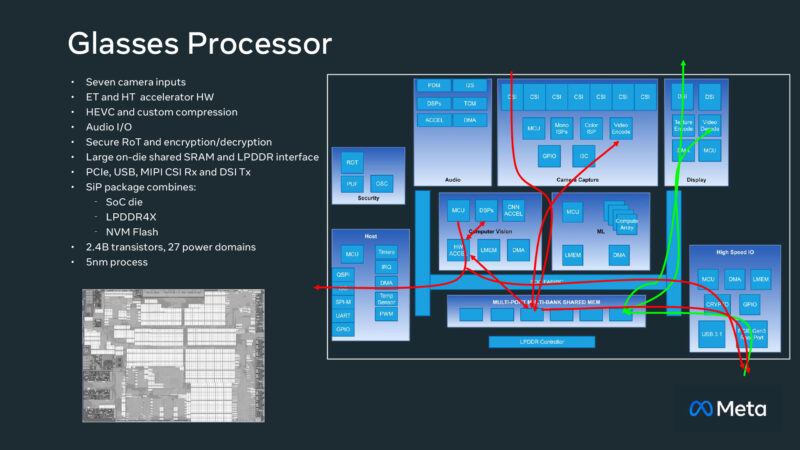

The glasses processor handles all the eye and hand tracking, as well as the camera inputs. It’s a full SiP, with a SoC, LPDDR4X memory, and NVMe flash memory all on the same package. 2.4B transistors altogether, built on a 5nm process. Meta even put a secure root of trust in the chip, so all data that enters and leaves the chip is encrypted.

Imagery coming from the puck is HEVC encoded, so the glasses processor needs to decode it. Eventually it gets reencoded into a proprietary format for the display processor.

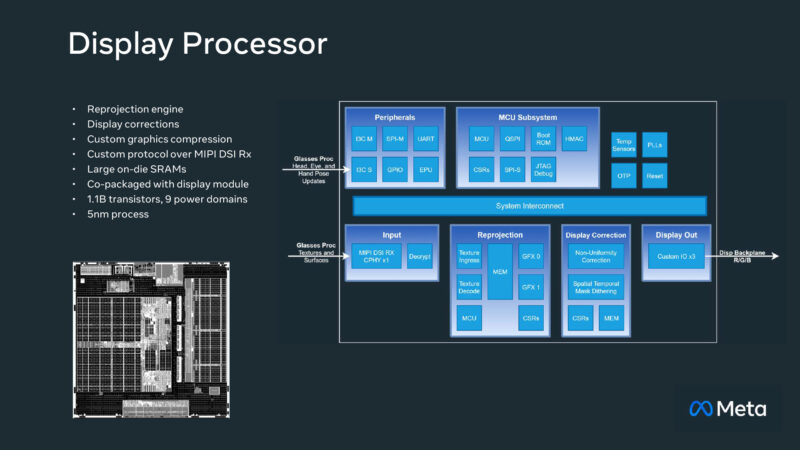

There are 2 display processors, one for each eye. Reprojection (time warp) takes place here. There is no external memory here, so everything is kept in on-die SRAM. Which means the SRAM is atypically large here.

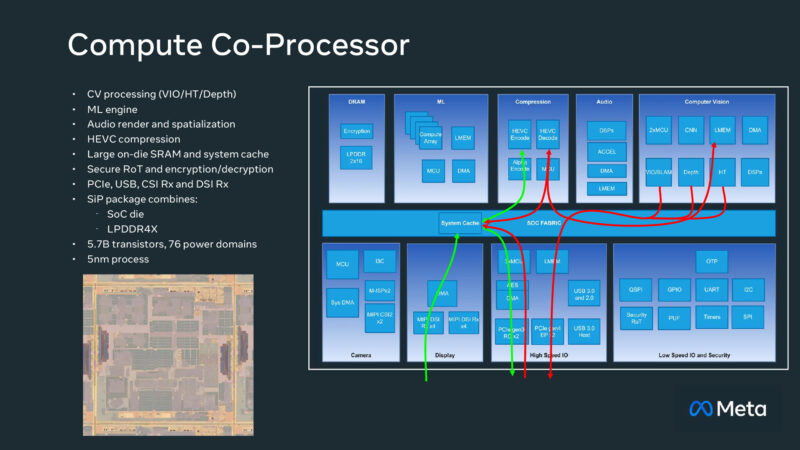

Finally, there is the compute co-processor in the puck. This is the most powerful processor with the greatest power and heat budget. Computer vision processing, ML execution, audio rendering, HEVC encoding, and more all take place here. This is another chip with a relatively large on-die SRAM cache. The overall chip is comprised of 5.7B transistors and built on a 5nm process; it’s packaged with LPDDR4X memory.

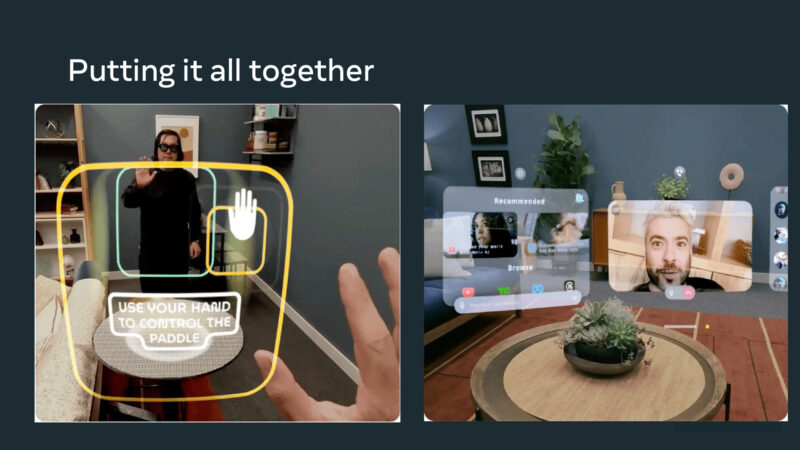

Put it all together, and you get the Orion glasses.

Great… More glass-holes…

We need laws restricting these to enclosed private property owned by the user.

Just because some idiot is willing to give Meta 24/7 biometric/behavioral data to feed their marketing/manipulation machine does not mean every other person around them has given consent.