Third up on today’s CPU track is IBM. Big Blue is at the conference to talk about its latest generation Power architecture chip, the Power11.

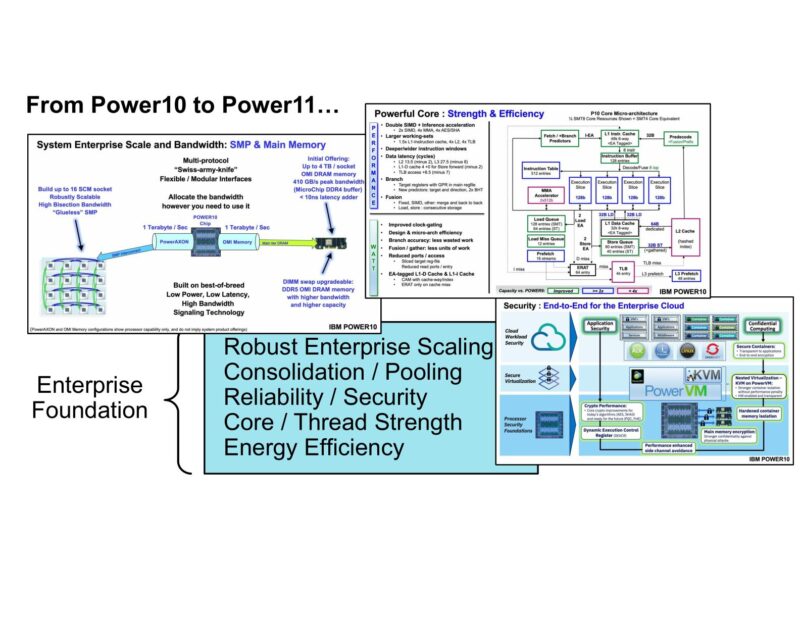

IBM starts off by recapping Power. Why it exists, and what IBM’s goals are for the processor and architecture. IBM is very system-focused, rather than focusing on selling just CPUs. 1P and 2P systems, all the way up to 16P “glueless” systems.

IBM starts off by recapping Power. Why it exists, and what IBM’s goals are for the processor and architecture. IBM is very system-focused, rather than focusing on selling just CPUs. 1P and 2P systems, all the way up to 16P “glueless” systems.

We are covering these live, so please excuse typos.

IBM Power11 at Hot Chips 2025

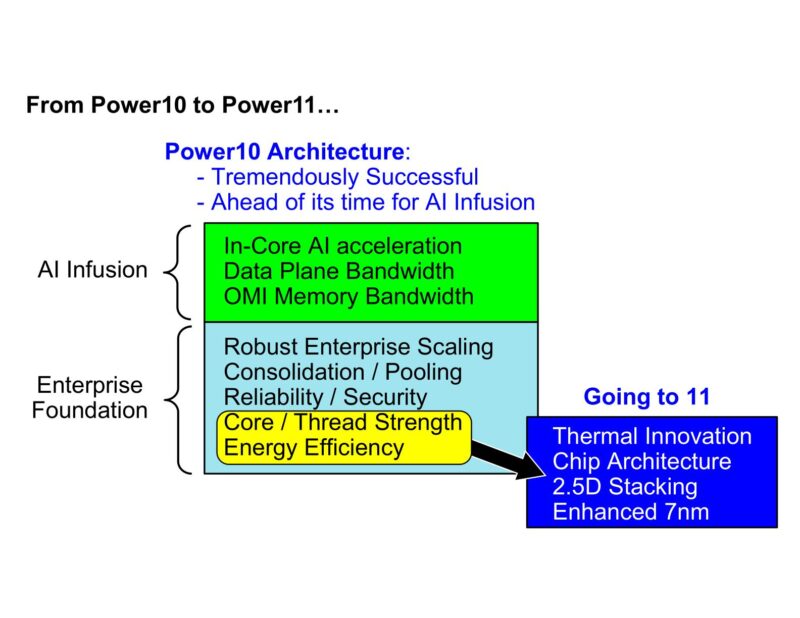

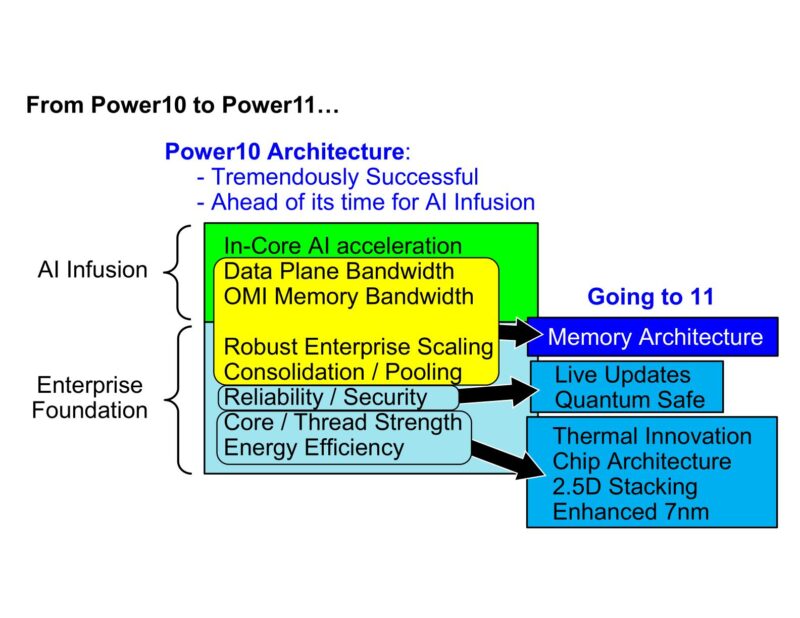

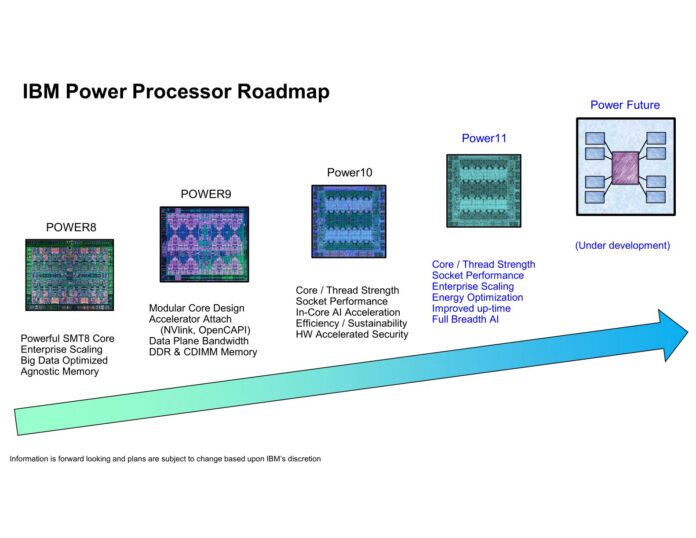

Recapping the Power release history, Power10 has proven to be very successful for IBM, “beyond our wildest dreams.” As a result, Power11 is not a substantial change from Power10; it builds upon Power10 rather than replacing large parts of it. This also means that there’s not as much new here as there have been in past Power presentations – or even other Hot Chips presentations.

To note: Power11 systems have already launched. So this Hot Chips presentation is more to bring the crowd up to speed than to blow everyone’s minds with new information.

IBM’s philosophy is fewer, larger cores, and then scaling up the number of cores as necessary.

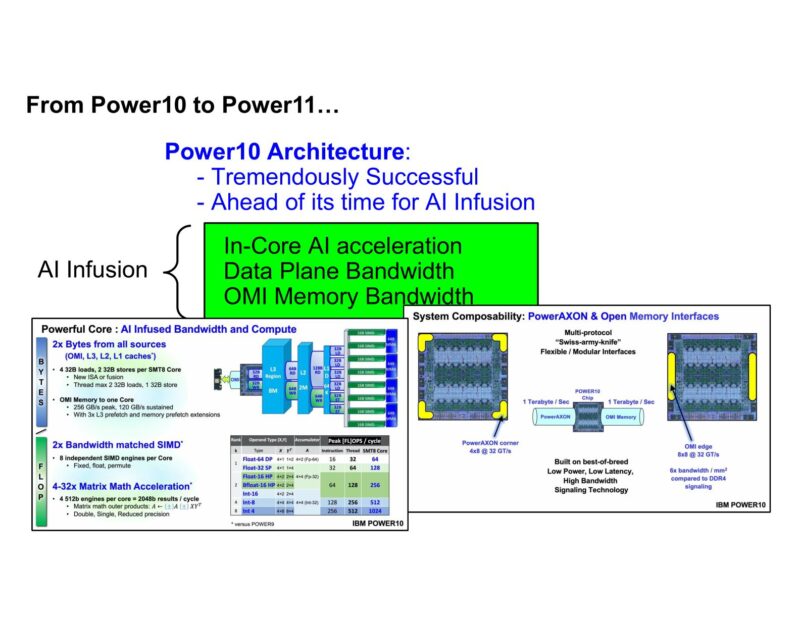

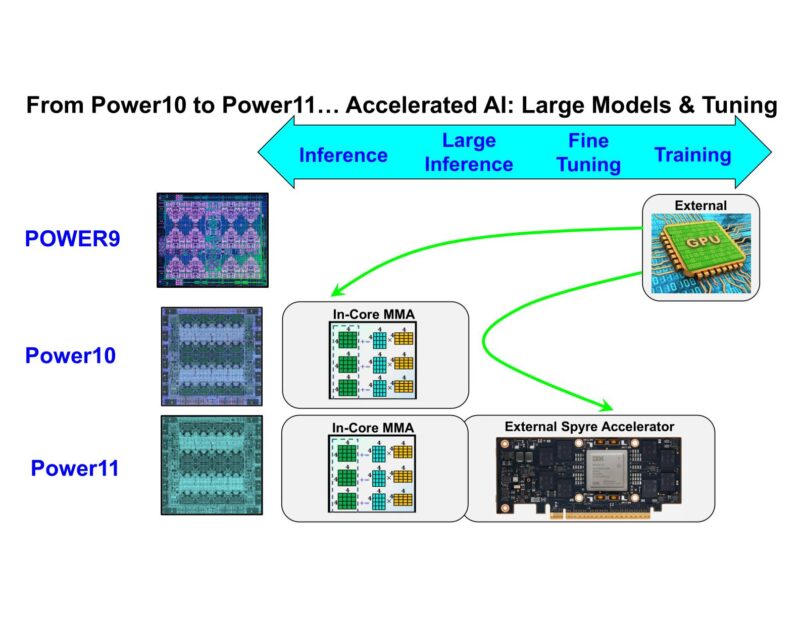

One of the big changes coming from Power10? The need to integrate AI into the processor cores.

In some respects, IBM was already ahead of the curve here with their matrix multiplication engine in Power10. But, of course, that’s not enough.

In some respects, IBM was already ahead of the curve here with their matrix multiplication engine in Power10. But, of course, that’s not enough.

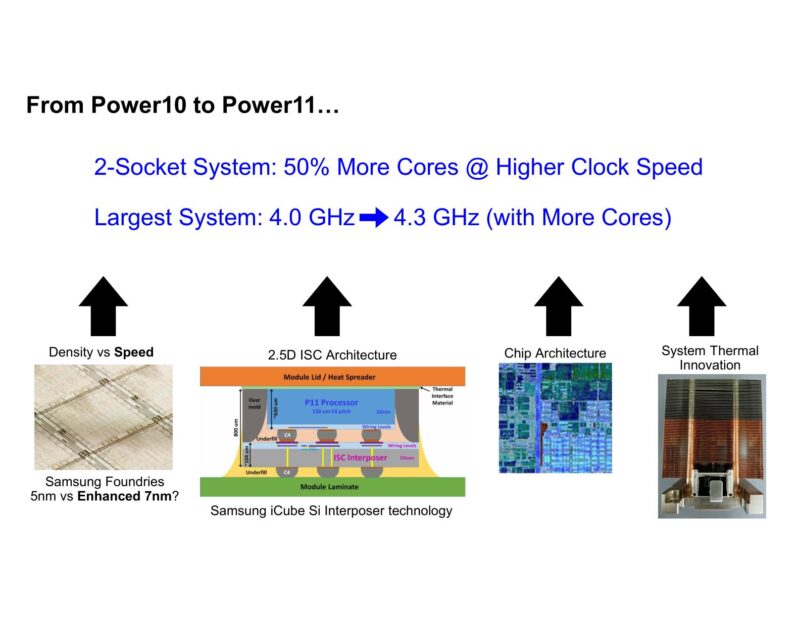

Power10 was built on Samsung 7LPE. Power11 stays on 7nm (based on feedback from clients), so there was a focus on speed instead of density. As a result, it’s built on a newer iteration of Samsung’s 7nm technology.

Power11 also goes to a stacked design. IBM is using a silicon interposer, also based on Samsung fab offerings.

Besides making a handful of core architecture changes, there has been a focus on the full system stack for Power11. This means working on everything from quantum safety for resilience against future attacks, up to improving how to go about deploying updates to systems.

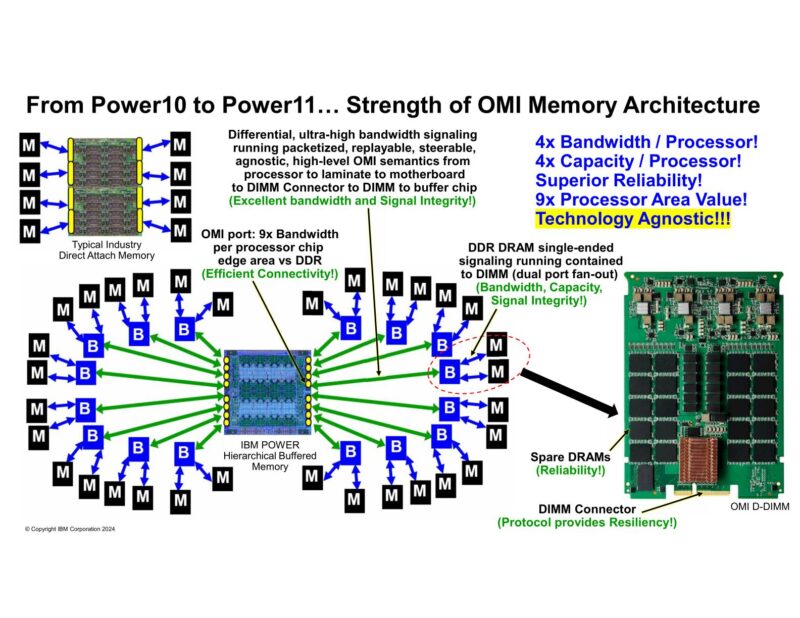

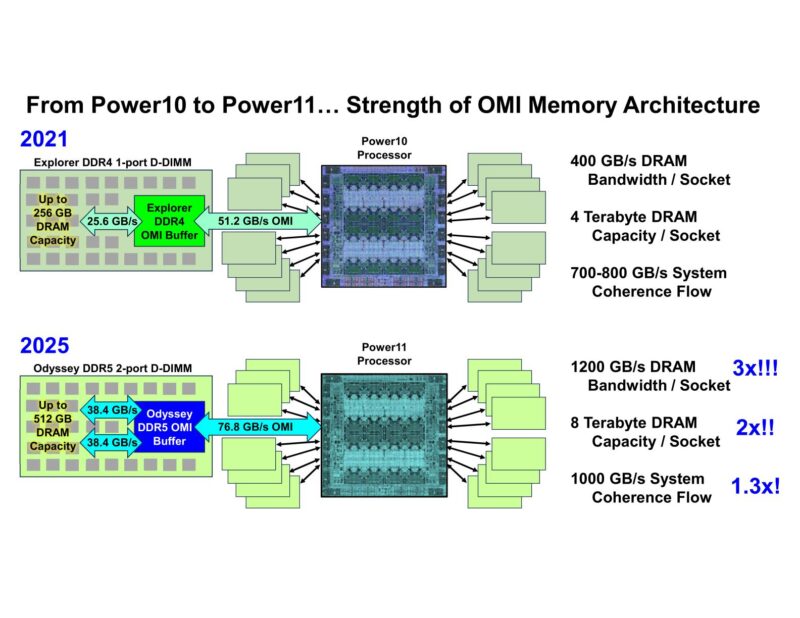

Bigger still are the upgrades to the memory subsystem for Power11, which IBM calls their OMI Memory Architecture. The hierarchical memory architecture means that one chip has up to 32 DDR ports of DDR5 memory. 38.4Gbps fabric speeds, ultimately leading to a customized memory form factor, the OMI D-DIMM.

IBM isn’t very bullish on HBM, by the way. Not that isn’t fast (it is), but it’s relatively low in capacity. IBM wants it all: they want 8TB of DRAM and >1TB/second of memory bandwidth. OMI can get there, all building on top of classic DDR5 memory. These OMI buffers add 6 to 8 nanoseconds of latency, according to IBM.

Power11 will also bring improved support for external PCIe accelerators. IBM has their own Spyre accelerator here.

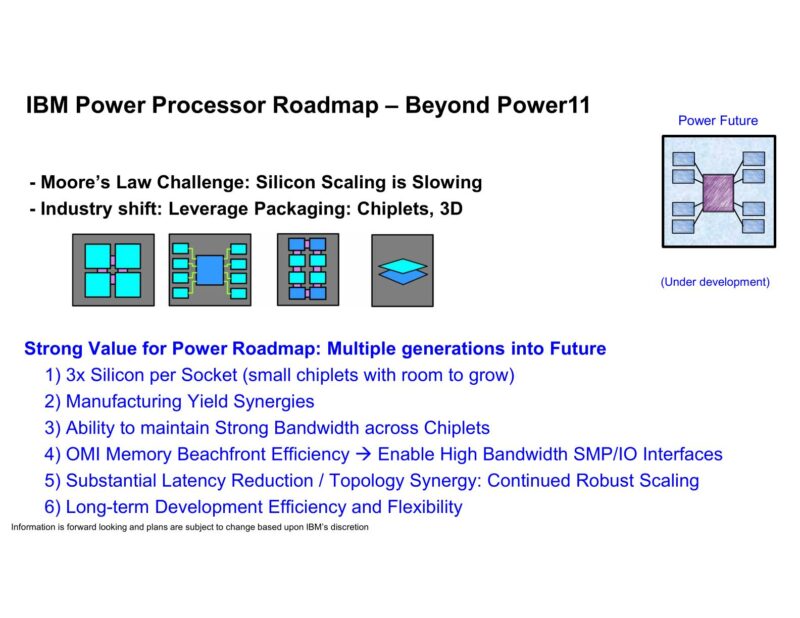

And, of course, IBM isn’t stopping with Power11. The next generation of Power – Power Future – is under development. IBM has to design their next chip with industry shifts in mind, both with regards to use cases and what technologies are available to build future chips. In short, like everyone else, IBM can’t rely on smaller process nodes to deliver large performance and density uplifts.

Besides immediate manufacturing concerns, there’s also a focus on bandwidth. The use of chiplets brings new challenges with regards to how much chip edge (beachfront) property is available. This is made all the more complex when so much bandwidth is needed just to attach the chiplets to each other. OMI is seen as one solution to that.

For those looking to Intel’s plans for 2026 CPUs, since they appeal to a broader market, we went into that in our Substack just after publishing this.

Over the last 30 years it has become evident open source software can compete in quality with proprietary systems such as IBM i, AIX and Microsoft Windows.

Open source means one company doesn’t fund all the development. Costs are shared among many entities. This is important because IBM is not rich enough to develop all the software themselves.

However, open source requires a mind share that includes many developers and companies. To enjoy such a mind share requires scalable hardware from the lowest entry level up to the largest enterprise. Power 10 and 11 have the high-end performance but lack an entry-level desktop suitable for use by an individual developer.

As a result, open source has ignored Power to the point architecture-specific optimisations are missing and many useful projects don’t build out of the box. The solution in my opinion is not for IBM to directly fund development of gcc and other important projects, but to make a cost-competitive entry-level system affordable to individual developers.

Said another way, it is hard to underestimate how much ARM in the datacenter benefited from Raspberry Pi on the desktop.

There is a cost-effective way to access Power-based systems already to run AIX, IBMi and or Linux operating systems for developers. It is called PowerVS – a Power virtual server in the IBM cloud. This starts from £2 or $3 or €3 per day for an admittedly tiny VM.

Thought I recognized that name lol

$3/day is over $1000/year which is not cost competitive with Raspberry Pi. Also I think you get much different levels of hobbyist investment with physical hardware you can hold in your hand vs a tiny VM in a cloud somewhere.

@Eric a Power 9 can be had for somewhere between a few grand (for just the motherboard and CPU) to just over U$10K for a more impressive system. For Power 10 it starts at U$30K, which is too much for a shareware developer; probably not too much if you plan on selling your software.

So, you’re not entirely out of luck.

I’d like an IBM Z15 (or greater) EATX motherboard, with just one CPU. They aren’t selling their Telum II that way.